The Stories behind the Songs

Living in Christleton singer/songwriter Bill Malkin performs as a solo artist, in a duo with John Sylvester (Malkin & Sylvester), and with ‘The band Wagon’ … an informal collective of musical friends, the core of which is John Sylvester and Dave Russell … as well as (from time to time) Paul Reaney, Chris Lee and Graham Bellinger.

You can enjoy the stories behind songs here, learn the words, read the chord symbols and sing along. Or just listen to the mp3 files and watch the video.

CHOCOLATE CHARLIE

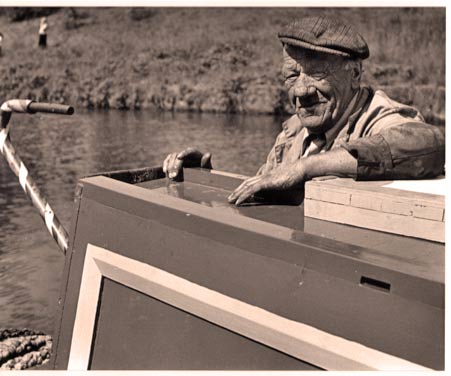

Charlie Atkins (known as Chocolate Charlie) was one of the most colourful characters of the ‘narrow boat era’ and would have passed through and visited Christleton on numerous occasions.

Charlie was born in 1902 into a boating family at Moss Pool Lock on the Newport Branch of the Shropshire Union Canal. He learned his boating skills on the Shroppie Flys until, at the age of 17, he took over his own boat, the horse boat ‘Skate’. In 1951 he became master of the ’Mendip’.

Built in 1948 by W J Yarwood & Sons, Northwich, the Mendip had a composite hull of iron sides and wood bottom. Her current engine was an 18 bhp Lister FR2.

Charlie’s association with this boat was to last for more than 30 years, as he worked the waterways between the North West (Ellesmere Port) and Birmingham, carrying loads of chocolate crumb to the Cadbury’s factory at Bourneville . The journey carrying a 25 ton load, involved 50 locks and took 14 hours. In a normal working week,

Legend has it that he often gave out ‘chocolate chips’ to children along the way who would wait for him to pass by. Hence his nick name ‘Chocolate Charlie’.

When the chocolate crumb trade finished in 1962, Charlie and ‘Mendip’ joined the British Waterways’ Anderton-based fleet. Trade was in aluminium ingots from Manchester to Wolverhampton, and feldspar (a basic pottery material) from Weston Point to Stoke-on-Trent, with a return load of coal to Seddon Salt at Middlewich. Later, grinding sand was carried locally for I.C.I. In 1963 ‘Mendip’ was transferred to British Waterways Board and the following year was leased to Willow Wrens. In November 1967, when the manager of Willow Wrens formed his own company, the Anderton Canal Carrying Company, Charlie and ‘Mendip’ joined them, staying until 1974.

Her last load was transporting concrete piles used to reinforce canal banks at Calf Heath. Once the ‘Mendip’ and Charlie had finished their working lives, they moored up at Preston Brook. It was during these years, with the rising interest in canals, that Charlie appeared in various television programmes which earned him modest national fame.

In 1976, he was reverently described in a national boating magazine as follows: “At 74, he still has the same tanned, weather-beaten face, creased with almost as many lines as miles of canal he has travelled; the same deep-set twinkling eyes, always smiling and the same optimism.”

As the area round Preston Brook began to be developed, it was suggested that both man and boat should move to Ellesmere Port as a sort of floating resident caretaker at the Boat Museum. Charlie was considering it when, because of ill health, his doctor ordered him to move off the boat. He went to live with his son in Birmingham. In the meantime, the boat was kept at Preston Brook as it was hoped he would return to it. Sadly he didn’t and he died in June 1981.

Following his death, Harry Arnold said of him in Canal and Riverboat, “He was a gentleman in the proper sense of the word and his death is like the closing of a door on another era of canal history. Many of us will miss the twinkling smile and the shake of the head, but there will be many times with Charlie Atkins that will never be forgotten”.

In 1993 the British Waterways presented the ownership of ‘Mendip’ to the Boat Museum at Ellesmere Port where she is still to this day.

CHOCOLATE CHARLIE

The Story: Chocolate Charlie & The Mendip

Charlie Atkins (known as Chocolate Charlie) was one of the most colourful characters of the ‘narrow boat era’ and would have passed through and visited Christleton on numerous occasions.

Charlie was born in 1902 into a boating family at Moss Pool Lock on the Newport Branch of the Shropshire Union Canal. He learned his boating skills on the Shroppie Flys until, at the age of 17, he took over his own boat, the horse boat ‘Skate’. In 1951 he became master of the ’Mendip’.

Built in 1948 by W J Yarwood & Sons, Northwich, the Mendip had a composite hull of iron sides and wood bottom. Her current engine was an 18 bhp Lister FR2.

Charlie’s association with this boat was to last for more than 30 years, as he worked the waterways between the North West (Ellesmere Port) and Birmingham, carrying loads of chocolate crumb to the Cadbury’s factory at Bourneville . The journey carrying a 25 ton load, involved 50 locks and took 14 hours. In a normal working week,

Legend has it that he often gave out ‘chocolate chips’ to children along the way who would wait for him to pass by. Hence his nick name ‘Chocolate Charlie’.

When the chocolate crumb trade finished in 1962, Charlie and ‘Mendip’ joined the British Waterways’ Anderton-based fleet. Trade was in aluminium ingots from Manchester to Wolverhampton, and feldspar (a basic pottery material) from Weston Point to Stoke-on-Trent, with a return load of coal to Seddon Salt at Middlewich. Later, grinding sand was carried locally for I.C.I. In 1963 ‘Mendip’ was transferred to British Waterways Board and the following year was leased to Willow Wrens. In November 1967, when the manager of Willow Wrens formed his own company, the Anderton Canal Carrying Company, Charlie and ‘Mendip’ joined them, staying until 1974.

Her last load was transporting concrete piles used to reinforce canal banks at Calf Heath. Once the ‘Mendip’ and Charlie had finished their working lives, they moored up at Preston Brook. It was during these years, with the rising interest in canals, that Charlie appeared in various television programmes which earned him modest national fame.

In 1976, he was reverently described in a national boating magazine as follows: “At 74, he still has the same tanned, weather-beaten face, creased with almost as many lines as miles of canal he has travelled; the same deep-set twinkling eyes, always smiling and the same optimism.”

As the area round Preston Brook began to be developed, it was suggested that both man and boat should move to Ellesmere Port as a sort of floating resident caretaker at the Boat Museum. Charlie was considering it when, because of ill health, his doctor ordered him to move off the boat. He went to live with his son in Birmingham. In the meantime, the boat was kept at Preston Brook as it was hoped he would return to it. Sadly he didn’t and he died in June 1981.

Following his death, Harry Arnold said of him in Canal and Riverboat, “He was a gentleman in the proper sense of the word and his death is like the closing of a door on another era of canal history. Many of us will miss the twinkling smile and the shake of the head, but there will be many times with Charlie Atkins that will never be forgotten”.

In 1993 the British Waterways presented the ownership of ‘Mendip’ to the Boat Museum at Ellesmere Port where she is still to this day.

The Song: Chocolate Charlie (Bill Malkin)

Hey, hey, the children say Chocolate Charlie’s coming our way

A G D

Bringing packets of chocolate chips, bringing them down on the old Mendip

D A G D

Charlie lived in a narrow boat home, cooked his food on a little coal stove

D A G D

Smoked a pipe, twisted his beard, wore a cap on the back of his head

Chorus

Charlie laughed, danced and sang, worked his life a Cadbury man

Carried the load the best he can, from Ellesmere Port to Bourneville Town

Chorus

Children they all knew the sound, when Charlie wound his windlass round

A simple Shropshire Union Man, doing the best he can

Chorus

The leaves all rustle, grass it grows, blackbird singing in the hawthorn row

The rooks and the ravens and the carrion crows, they all know his name

Chorus x2

Chocolate Charlie (Bill Malkin)

Charlie Atkin’s life is celebrated in Bill Malkin’s song ‘Chocolate Charlie’. Watch the following You Tube video

THE BIRKENHEAD DRILL

The Story: Women and Children First - The Silent Heroes of Birkenhead

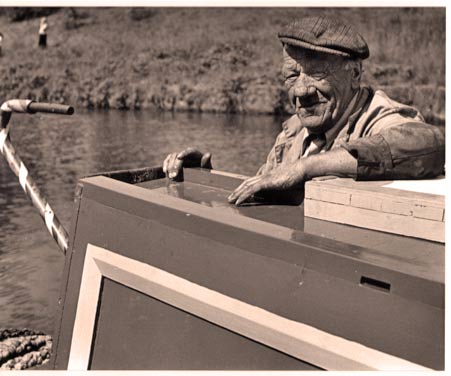

The naval tradition of ‘women and children first had its origin with the sinking of H.M.S. Birkenhead off the coast of South Africa in1852. The events of that tragic night were brought to popular attention and immortalized in Rudyard Kipling’s famous poem "Soldier an' Sailor Too".

The story began in January 1852 when, under the command of Captain Robert Salmond, the Birkenhead left Portsmouth taking troops to fight in the Frontier War in South Africa.

The Birkenhead, one of the first iron hulled paddle steamers in service travelled to southern Ireland, before heading for the Cape on 17th January. The troops onboard included drafts of Fusiliers, Highlanders, Lancers, Foresters, Rifles, Green Jackets and assorted other regiments.

After taking on fresh water and supplies the Birkenhead steamed out of Simon's Bay near Cape Town, in the late afternoon of 25th February, with about 634 men, women and children on board. With weather conditions perfect, a clear blue sky and a flat and calm sea, the Birkenhead continued steadily on her passage.

Captain Salmond had received orders to use all possible haste to reach his destination of Algoa Bay. In order to speed up the trip he decided to hug the South African coastline as closely as possible. This course kept the Birkenhead within approximately three miles of the coast, maintaining a speed of approximately 8 knots.

It was in the early hours of 26th February, approaching a rocky outcrop called Danger Point, some 180 km from Cape Town that disaster struck. With the exception of the duty watch, everyone else was tucked up asleep in their quarters. The watch were scanning the clear glowing waters ahead and the Leadman had just called “Sounding 12 Fathoms” when the Birkenhead rammed an uncharted rock.

The churning paddle wheels of the Birkenhead drove her on with such force that the rock sliced through into the hull ripping open the compartment between the engine-room and forepeak. Water flooded into the forward compartment of the lower troop deck filling it instantly. Hundreds of soldiers were trapped and drowned in their hammocks as they slept.

All the surviving officers and men who could, assembled on deck. Some of the soldiers stood barefoot dressed only in their night-clothes, others less lucky were naked and many with the injuries sustained as they clawed their way from the flooded troop quarters. The senior officer on board, Lieutenant-Colonel Seton of the 74th Royal Highland Fusiliers took charge of all military personnel. He immediately summoned his officers around him and stressed the importance of maintaining order and discipline amongst the inexperienced soldiers.

Distress rockets were fired, but there was no help at hand. Realising the hopeless position they were in, the captain ordered the lifeboats to be lowered. Much of the lowering equipment would not function, due to a lack of maintenance and a thick layer of paint that clogged the mechanisms.

That night under a clear starry sky the great naval tradition of “women and children first” was established as eventually two cutters and a gig were launched and the seven women and thirteen children were rowed away from the wreck to safety. The horses were cut loose and thrown overboard. Only then did Captain Salmond shout to the men that everyone who could swim must save themselves by jumping into the sea and make for the boats.

Lieutenant-Colonel Seton, the soldier's commanding officer, quickly recognised that such a rush would mean that the lifeboats could be swamped and the lives of the women and children onboard would thus be endangered. He drew his sword and ordered his men to stand fast. The untried soldiers did not move even as the ship split in two and the gallant company slipped down into the waves.

The Birkenhead sank only twenty-five minutes after she had struck the rocks, only the topmast and sailcloth remained visible above the water with about fifty men still clinging to them. The sea was full of men desperate for anything that could float. Death by drowning came quickly to many of them, but the more unfortunate were taken by the Great White sharks.

The next morning the schooner Lioness reached the lifeboats rescuing those onboard, after which she headed for the scene of the disaster reaching the wreck that afternoon, picking up the remaining survivors. Of the 634 people onboard the Birkenhead, only 193 were saved.

The song ‘The Birkenhead Drill’ written by Bill Malkin and Graham Bellinger tells the story:

The Song : The Birkenhead Drill

(by Bill Malkin & Graham Bellinger)

John Laird it's said, built the finest ships

G

That sailed from Liverpool

A

And I’ll tell you a tale of one that sailed

G D

The finest of them all

With hull of steel and paddle wheel

Birkenhead the name she bore

With passengers and crew, and soldiers too

She was bound for the Frontier War

Neath a silent moon and the Southern Cross

Too late the lookout’s shout

On a hidden rock off Danger Point

She had her heart torn out

The sea gushed in, her stern rose high

The smoke stack crashed and burned

Came the Captain’s orders to abandon ship

Woman and children first

Bm A

(Ah) to stand and be still to the Birkenhead Drill

Bm A

Is a damn tough bullet to chew

Em Bm

But they did it those Jollies, Her Majesties Jollies

G A D

Soldiers and sailors too

Bm A

They stood those Jollies, Her Majesties Jollies

Bm A

Stood so silent and still

Em Bm

They did those Jollies, the Birkenhead Jollies

G A D

Soldiers and Sailors too

Audio: The Birkenhead Drill

(by Bill Malkin & Graham Bellinger)

Listen to the music

THE SALFORD SIOUX

The Story: The Salford Sioux

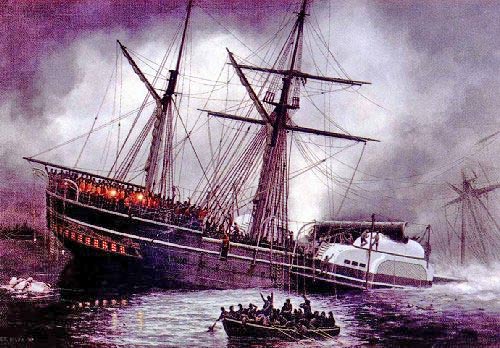

One of the most colourful figures of the American Old West, Buffalo Bill became famous for the shows he organized with cowboy themes, which he toured in Great Britain and Europe as well as the United States.

During the winter of 1887-88 this show arrived in Manchester and set up camp on the cold damp banks of the River Irwell.

They performed nightly to packed crowds in what was the biggest indoor arena ever constructed in Western Europe. Sioux warriors (some of whom had fought Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn) and their cowboy counterparts would recreate classic scenes from the Wild West, and perform daring acts of horsemanship.

The show was so popular that it took a break from its world tour to stay for six months in Salford.

Their stay was, however, surrounded in some mystery …

After the 6ft 7ins warrior ‘Surrounded' died of a chest infection in his teepee on Salford Quays his body was taken to Hope Hospital, where it promptly vanished. It was never buried, but there is no record of it being moved, and nobody admitted to taking it.

Also during their stay one small Sioux girl was baptised at St Clement's Church before slipping out of the history books. When the show moved on to Chester some of the Indians chose to remain in Salford....and to this day some of their descendants (known as the Salford Sioux) continue to live in Greater Manchester.

The story of the Salford Sioux is remembered in Bill Malkin’s song of the same name.

Black Elk

The Song : The Salford Sioux

Words and music by Bill Malkin

On pastel painted ponies, with feathers and with bows

G D C B7

Their pride could not be stolen, as easy as their homes

G D Am C

Those sons of South Dakota took solace in the glow

G D C B7 Em

Of cheering crowds that came to see Bill Cody’s Wild West Show

For crowd delight they whooped and wailed

and cut the Pale Face down

In the dust of Salford Quays, around the totem pole

In the shadows of the smoke stacks and the blackened factory walls

The ragged rows of teepees watched the dirty Irwell flow

Chorus:

Am Em Am

Come and see the covered wagons roll

C B7 Em

Before the final curtain has to fall

The forests and the prairies

The eagles flying high

The spirits of the fallen ones, dancing wolves that cry

The ghost of mighty Black Elk, and the savage Salford Sioux

Still roam at night in Buffalo Court and Dakota Avenue

Audio: The Salford Sioux

by Bill Malkin

Listen to the music

ROBERT CADMAN

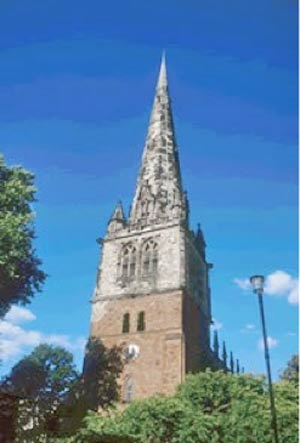

The Story: Robert Cadman – Icarus of the rope

Cadman, a steeplejack who lived in Shrewsbury in the 18th C, and earned extra money by tightrope walking.

On February 2nd 1739, at the age of 28, he attempted his most daring feat and set about ‘sliding’ across the River Severn on a rope stretched from the tower of St Mary's Church to Gaye Meadow on the other bank of the river - a distance of around 800 feet and over 200 feet high at the tower. After much initial merriment, and several drinks at the local tavern, Cadman (accompanied by a troupe of ‘jesters, knaves and jugglers’) set about his task.

He began by walking up the rope firing pistols and performing tricks. Then he fastened a wooden breastplate (which had a groove in it) to his leather doublet, lay on the rope and prepared to slide down to earth.

Unfortunately the rope broke and he fell to his death.

His wife was waiting to collect the money that the ladies and gentlemen of Shrewsbury might kindly donate. When she was told that he ‘had been dashed to pieces’ she dropped the donations and ran to his body.

It is not known how many donations were made on the day that Robert Cadman died or what indeed happened to his wife.

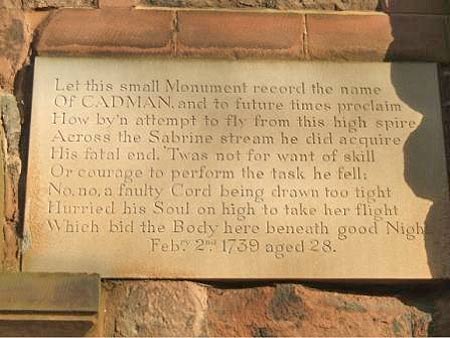

He was buried in St Mary's Church, where a plaque in his memory may still be found on the wall to the right of the main entrance door. It reads:

Of Cadman, and to future times proclaim

Here, by an attempt to fly from this high spire

Across the Sabrine stream, he did acquire

His fatal end. 'Twas not for want of skill

Or courage to perform the task, he fell :

No, no a faulty cord, being drawn too tight

Hurried his soul on high to take her flight,

Which bid the body here beneath good night

Feb.2nd 1739 aged 28.

The Song : The Ballad of Robert Cadman

The story of Robert Cadman lives on in the song written by Bill Malkiin and John Sylvester

Did you hear the tale of Cadman who lived in Shrewsbury town

C G D

Master of the high-wire, high above the ground

D C G D

Jesters naves and jugglers, dancing in the street

C G D

Plans and preparations finally complete

Crowds had all gathered to see if he could fly

Across the Severn River to the other side

Across the Severn River to the other bank

His doublet made of leather

breast-plate made of plank

Chorus

A G D

He was not short of courage, was not short of skill

A G D

From St. Mary’s steeple Cadman would prevail

D C G D

Bells around his ankles, bells around his wrists

D C G D

In colours so appealing, performing clever tricks

Flagons filled with cider, flagons filled with ale

From St. Mary’s steeple Cadman would prevail

He was not short of courage, was not short of skill

It was a faulty cord they said, the records clearly tell

by Bill Malkin and John Sylvester

Listen to the music

CHRISTLETON MILL

Records show that the Mill was owned by the family of Thomas Ball and one imagines that it would have played an important role in the local agricultural economy .

Although it is not certain, some say that it was destroyed during the Civil War in an attack on Christleton. This attack made by Royalist soldiers led by Price Rupert in 1645, was in revenge for an ambush that had taken place in the area of what is today, the ‘Sainsbury’s roundabout’.

For quite some time, the Roundheads had been using Christleton as a base while besieging the Royalists in Chester. About nine months before the Battle of Rowton Moor, a Royalist force of 1300 horse and men road out of Chester to try to drive Parliamentarians out of the village. Watchmen looking out from the steeple tower of St James church had seen their approach and raised the alarm. An ambush was quickly set up and in the proceeding skirmish, heavy losses were inflicted on the King’s men. 200 soldiers were killed including 3 Colonels.

In revenge,Prince Rupert lead a strong force to try to crush Cromwell’s men but the crafty Roundheads had vacated Christleton. The Royalists found no enemy in the village and in their frustration, proceeded to burn it to the ground. The local mill would have been amongst the many buildings destroyed.

These events are recounted in Bill Malkin’s song ‘ Christleton Mill’

The Song: Christleton Mill (Bill Malkin)

Dm F

At the back of St. James, there is a small hill

C Dm

Where once it was said there stood a windmill

F

Owned by the family of one Thomas Ball

C Dm

A building so fine, it stood fifty feet tall

It took all the harvests, ground all the corn

Paid all its taxes to Christleton Hall

Would still be standing, so they all say

But for what happened on that fateful day

The Royalists rode out from Chester town

Into an ambush, so many gunned down

200 soldiers, officers and men

Fell on the highway in bloody Boughton

Chorus :

F C

And the cuckoos cry out, and the nightingales sing

Dm Am

While bells of St. James continue to ring ( repeat )

Revenge was swift, someone had to pay

Rupert’s brave men would have the last say

And though the rebels could not be found

They set fire and burned old Christleton down

And without reason, on the same day

They burned down the mill, and went on their way

Chorus.

THE 'BALLAD OF ROWTON MOOR'

The battle of Rowton Heath took place in and around Christleton on 24th September 1645, some 2 miles to the south-east of Chester. This was a mainly cavalry action lasting sporadically over a whole day and extending across three main locations, as the Roundheads forced the Royalist forces back towards the city. Viewing the battlefield from the Phoenix Tower on the walls of Chester, Charles I saw his last substantial body of cavalry comprehensively defeated.

It was to be the last major battle of the Civil War. King Charles fled Chester but was soon captured, tried and eventually beheaded.

Christleton’s ‘Roman Bridges are thought to have been constructed in the latter part of the 15th Century. They get their name from the fact that Roman bridges of timber construction previously occupied this spot. They form part of a packhorse route that was the main thoroughfare from London to Chester, across the River Gowy and surrounding marshland. Reference to the significance of this packhorse route can be found throughout history. The Black Prince’s Register refers to “a grant of 20 shillings for the repair of the bridge of Hockenhull” and Ogibly’s Britannia Road Map of 1675 shows them clearly marked.

The legend of Grace Trigg, the Headless Woman, goes back to the time of the Civil War when Oliver Cromwell visited the area, his mission to wipe out the royalists. A family loyal to the king living at the nearby Hockenhull Hall fled in fear of their lives, leaving their maid Grace Trigg to look after all of the estates wealth. Grace, being a dutiful servant took it upon herself to hide the sliver and finery somewhere for safekeeping. She was captured by Cromwell’s men and tortured to find out where she had hidden the valuables, but being a loyal to her masters she never told.

It is thought that Grace managed to escape her captors and attempted to run along the packhorse route known locally as ‘the Roman Bridges’. Somewhere along the Roman Bridges the soldiers recaptured her and it is said that this struggle resulted in her beheading.

One version of the tale states that the soldiers intended to slit her throat but the deed was carried out with such force that the result was a near beheading, leaving her body and head barely attached. On many occasions since then Grace’s ghost has been sighted, walking with her head under her arm, in the area near to the Roman Bridges and along the old path from Hockenhull Hall to the public house now known as the Headless Woman

The Song - The Ballad of Rowton Moor (Bill Malkin)

In the firelight she fancied she saw soldiers marching

C Am

Banners flying, so brave and so young

G C G

And while the flames crackled she heard cannons crashing

D G

Heard their death cries as they fell one by one

Out in the fields, the harvest moon shining

Long grass still whispers of days that have gone

Memories of muskets that rust in the hedgerows

The battle they fought at old Rowton Moor

Chorus …

C G D G

And still they are standing, three Roman bridges

C G C D

Braving , the wind, the rain and the sun

G C G

Crossing the Gowy, leading from London

C G D G

All of life’s travellers, that pass one by one

In the flickering light of the last dying embers

She folded her blanket and went up the stairs

Alone with the shadows she lay there and wondered

Then slipped off to sleep in her four posted bed

Prince Rupert

Listen to the music